Working to Decrease the Impact of Dengue in Yemen

Dengue is a vector-borne viral infection that affects many parts of the world. With up to 100 million infections occurring annually, dengue has placed nearly half of the world’s population at risk. Dengue causes severe, flu-like symptoms and can sometimes progress to “severe dengue,” formally known as “hemorrhagic fever.” First identified in the 1950s, today it is known to majorly affect Asian and Latin American countries. Severe dengue is a leading cause of death and hospitalization in these areas. Dengue thrives in poorer urban and suburban areas but has been documented in wealthier tropical and subtropical countries, as well (“WHO | What is dengue?,” n.d.).

Our team is focused on the effects of dengue specifically in Yemen. Located on the Arabian Peninsula, Yemen has become plagued by dengue fever for several reasons. First and foremost, Yemen’s climate, which includes a prolonged rainy season, results in standing water – a favorite breeding spot for mosquitos (Maged Ahmed Al-garadi, 2015). Additionally, Yemen has been plagued by civil war since 2015, perpetuating the country’s poor infrastructure (Yemen country profile, 2019). The war has forced Yemen to funnel resources into other areas, neglecting to effectively monitor and control the spread of the virus. The inherently poor population of Yemen lacks the knowledge of how to combat and treat dengue (Maged Ahmed Al-garadi, 2015). Many communities have poor sanitation practices, perpetuating the spread of dengue.

As a team, we determined five problems present in Yemen that tie into the country’s dengue pandemic. One issue is the lack of vector prevention mechanisms. The WHO adopted a 5-year plan to increase the “preparedness and response activities for dengue fever prevention and control,” but their efforts are primarily focused on increasing and strengthening surveillance and detection. Just a small element of their efforts focus on vector-control through insecticide spraying (“WHO EMRO | WHO develops national strategy for dengue prevention and control | Yemen-news | Yemen,” n.d.). The Yemeni government is presently enveloped in civil war and gives little attention to providing its population prevention mechanisms.

A second issue present in Yemen is poor water infrastructure, particularly regarding water storage. Ongoing war has led to a “breakdown in safe water supply and sanitation services” (Shadoul & Taha, 2015). This poor infrastructure results in water shortages, forcing many residents to store water in open containers in and around the home, leading to the gathering of mosquitoes (“Drinking water systems under repeated continuous attack in Yemen [EN/AR] – Yemen,” n.d.). A third issue concerns the sanitation conditions present in Yemen. Again, due to civil war, conditions in Yemeni cities are poor. Mounds of uncollected garbage line the streets. This trash, combined with untreated sewage and the Arabian heat, has created the perfect storm for dengue-carrying mosquitoes to flourish (Burki, 2016).

A fourth issue plaguing the population of Yemen is indoor air pollution. Domestic use of biomass fuels increases the amount of indoor air pollution and heat in a household and structure. As a result, we hypothesized that the warmer climate in the house would attract mosquitoes, which thus increases the potential of any inhabitants to be infected with dengue. However, the article written by Biran, Smith, Lines, Ensink, and Cameron indicates that the resulting smoke and smog from burning biomass acts as a natural repellant of mosquitoes.

Our final issue of note, briefly touched on previously, is that of open water containers. Open containers with standing water need to be scrubbed at least weekly to minimize mosquito breeding. Mosquito larvae attach to the sides of the container and can survive there without surrounding water for up to 8 months. As a result, just emptying the water will not stop the larvae from hatching and maturing and later infecting inhabitants with dengue (“Zika, Mosquitoes, and Standing Water | | Blogs | CDC,” n.d.).

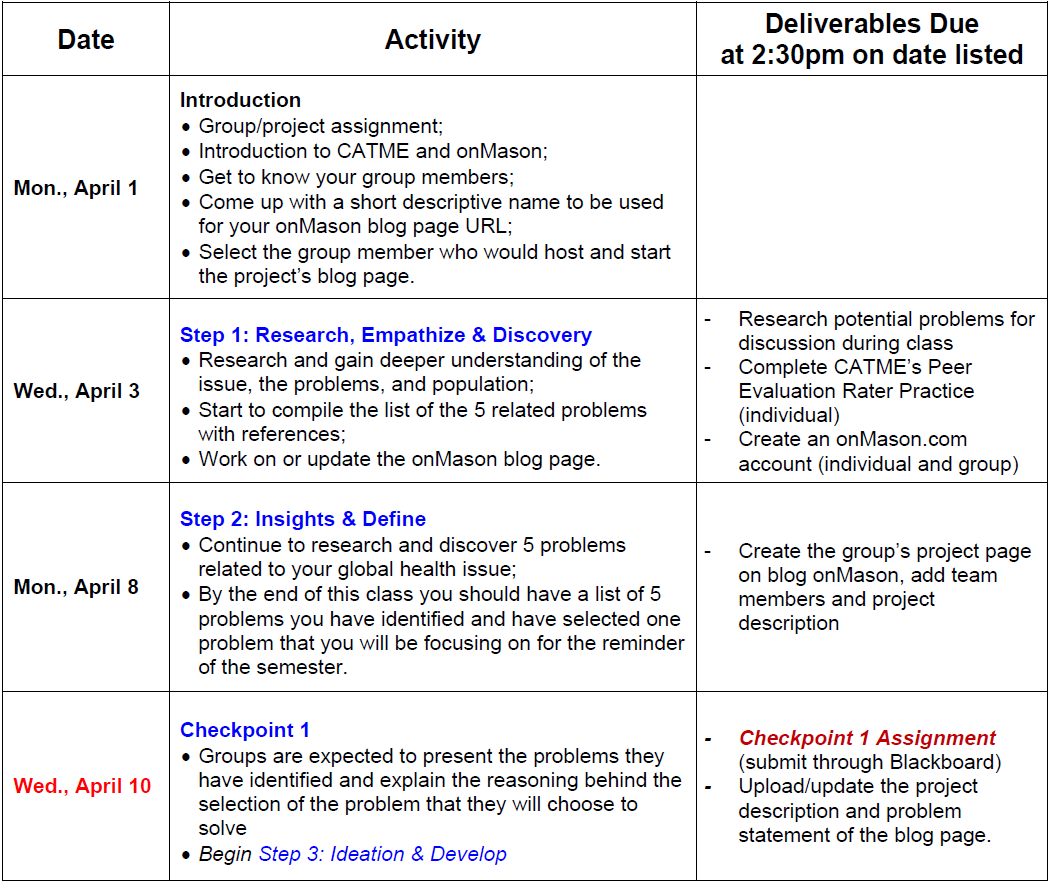

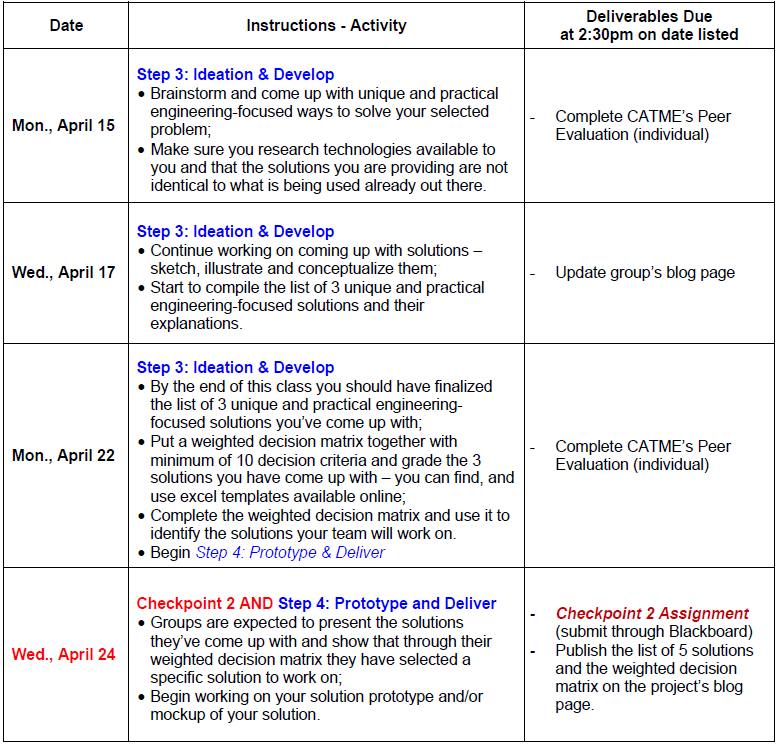

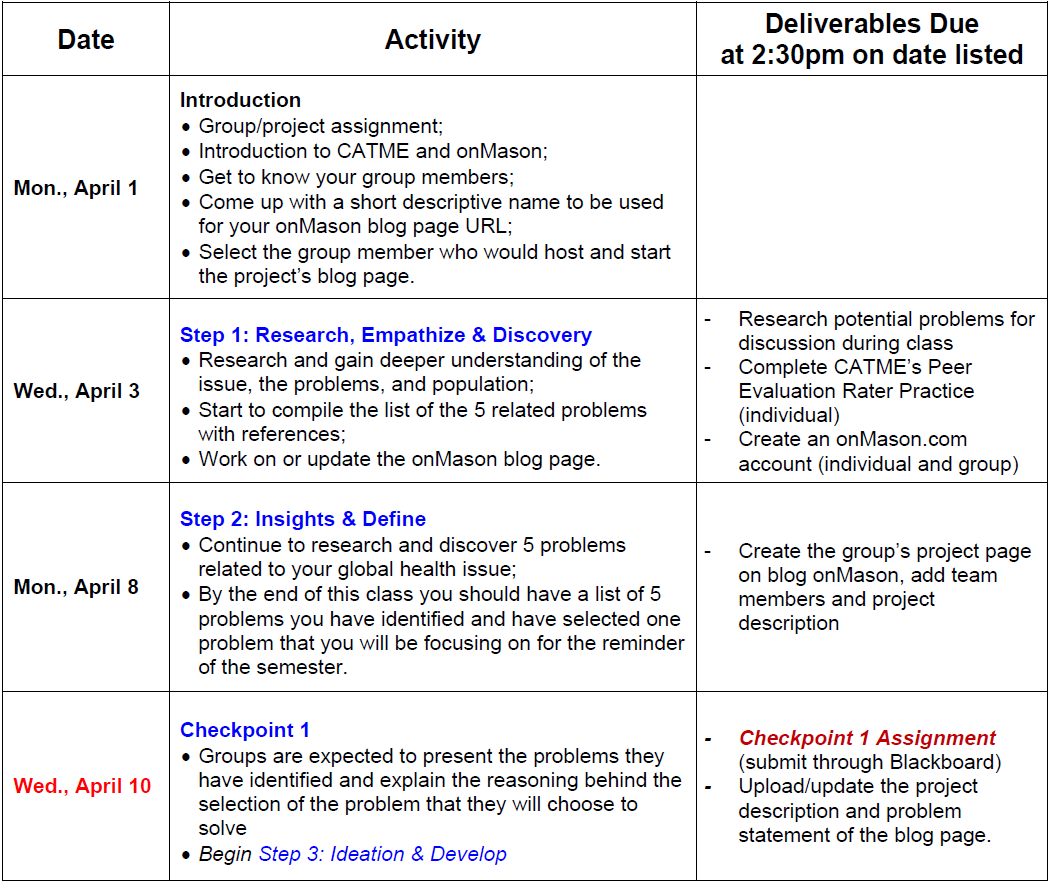

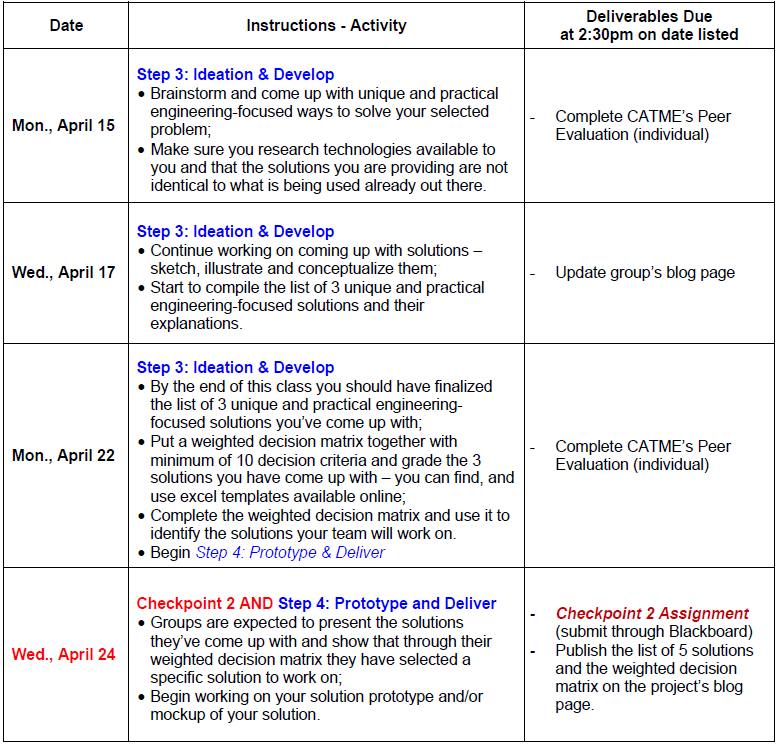

After concluding our preliminary research on these five issues, we came together to narrow the list down to a single issue. We created a decision matrix to help with this process.

| Protection Mechanisms | Water Storage | Sanitation | Indoor Air Pollution | Standing Water | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Prior Knowledge | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| (2) Ease of Research | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| (3) Significance | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| (4) Control | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Totals | 50 | 23 | 27 | 30 | 30 |

We chose four determining factors on which to rank each issue: our prior knowledge, ease of research, significance (or “does it matter?”), and control (or “can it even be done?”). We first gave weights to these factors, with four being most important and one being least important. Using a scale (from 1 to 5), we then went item by item, ranking each of the five issues on every factor. For example, our research found that indoor air pollution has very little impact on the high occurrence of dengue in Yemen; thus, it received the lowest significance rating. Standing water, on the other hand, proved to be a major contributor to high mosquito populations, so it received the highest significance rating.

As can be seen in our Totals column, the issue of lacking protection mechanisms stood out as the front-runner, receiving a rank of 5 in each category. Our prior knowledge of the subject is relatively high, having personal experience with various tools such as mosquito nets, preventative clothing, and insecticide sprays. This issue is relatively easy to research, as documentation on the matter appears to be abundant. The lack of protection mechanisms available to the Yemeni population carries a high significance in regard to the rising count of residents contracting dengue. Finally, this issue can be “controlled,” or at least lessened. Moving forward, our team will focus on developing several practical engineering-based solutions to address this problem.

Biran, A., Smith, L., Lines, J., Ensink, J., & Cameron, M. (2007). Smoke and malaria: are interventions to reduce exposure to indoor air pollution likely to increase exposure to mosquitoes? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 101(11), 1065–1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.07.010

Burki, T. (2016). Yemen’s neglected health and humanitarian crisis. The Lancet, 387(10020), 734–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00389-5

Drinking water systems under repeated continuous attack in Yemen [EN/AR] – Yemen. (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2019, from ReliefWeb website: https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/drinking-water-systems-under-repeated-continuous-attack-yemen-enar

Maged Ahmed Al-garadi, د. م. ا. ا. (2015). Epidemiological review of dengue fever in Yemen. International Journal of Advanced Research, 3, 1578–1584.

Shadoul, A., Taha, A. (2015). Yemen Conflict Report. WHO. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/yemen/WHO_Yemen_sitrep_no8_7_June_2015.pdf

WHO | What is dengue? (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2019, from WHO website: http://www.who.int/denguecontrol/disease/en/

WHO EMRO | WHO develops national strategy for dengue prevention and control | Yemen-news | Yemen. (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2019, from http://www.emro.who.int/yem/yemen-news/who-develops-national-strategy-for-dengue-prevention-and-control.html

Yemen country profile. (2019, February 18). Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14704852

Zika, Mosquitoes, and Standing Water | | Blogs | CDC. (n.d.). Retrieved April 9, 2019, from https://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2016/03/zikaandwater/